Place in Howard Thurman's Jesus & the Disinherited

how Jesus' love-ethic leads from policing segregation to neighborly belonging

In the first few months of the pandemic, cloistered on a hill in Maine and awaiting my first child’s birth, I read through a number of significant works by Black, Asian, Indigenous, and Latinx authors in theory and theology. I was curious how “place” — as a theoretical category and the fundamental matrix of real life and relationships — functioned in their work and imaginations. I wrote out a number of short essays summarizing what I saw in what I read. I am grateful share them here as part of an ongoing dialogue in the praxis for liberation. Thank you for being part of this community and conversation!

_ _ _ _

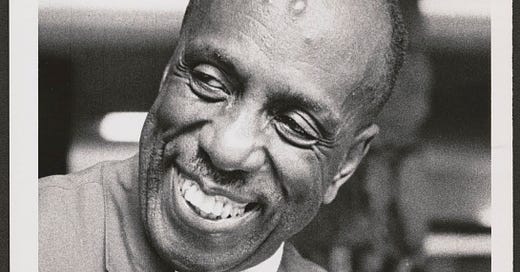

While living in San Francisco where he pastored the nation’s first congregation to explicitly encourage racial integration, Howard Thurman wrote his seminal text Jesus and the Disinherited—a book Martin Luther King Jr. reportedly carried with him throughout the Civil Rights Movement.

Thurman refused the version of Christianity offered in white America, and determined to provide an account of the religion of Jesus from the perspective of those “with their backs against the wall” which had not yet been articulated. Thurman sees this as a place-based contextual challenge:

“This is the question which individuals and groups who live in our land always under the threat of profound social and psychological displacement face. Why is it that Christianity seems impotent to deal radically, and therefore effectively, with the issues of discrimination and injustice on the basis of race, religion and national origin? Is this impotency due to a betrayal of the genius of the religion, or is it due to a basic weakness in the religion itself?”

It is something we must face here in our place, “our land.”

For Thurman, the roots of the problem begin in the separation of Christianity from the historical realities of its founder and professed Lord and Savior.

“How different might have been the story of the last two thousand years on this planet grown old from suffering if the link between Jesus and Israel had never been severed!…Jesus of Nazareth was a Jew of Palestine when he went about his Father’s business, announcing the acceptable year of the Lord.”

Jesus was not only a Jew but a poor Jew, and further, he was a poor Jew who “was a member of a minority group in the midst of a larger dominant and controlling group.” Thurman is reformulating the Christian faith by planting it back in the cultural and political environment of Jesus’ Palestinian home. Who he was in that place at that time matters to who we can be in our place and time. The parallel in conditions from the place and time of Jesus to the milieu faced by Black Americans under Jim Crow, coupled with Thurman’s intimate understanding of the psychological affects of oppression on the oppressed, leads him to reclaim the religion of Jesus as a “technique of survival for the oppressed.”

Thurman writes that segregated places are created as a means of control deployed by those who harbor hatred and hold uneven power. For the powerful group, boundaries remain porous, while those who are excluded must honor their arbitrary borders as a preordained state of nature:

“Two groups that are relatively equal in power in a society may enter into a voluntary arrangement of separateness. Segregation can apply only to a relationship involving the weak and the strong. For it means that limitations are arbitrarily set up, which, in the course of time, tend to become fixed and to seem normal in governing the the etiquette between the two groups. A peculiar characteristic of segregation is the ability of the stronger to shuttle back and forth between the prescribed areas with complete immunity and a kind of mutually tacit section; while the position of the weaker, on the other hand, is quite definitely fixed and frozen.” 31

The separateness whiteness imposes paradoxically produces fear in both groups. The strong convince themselves that maintaining well policed boundaries protects “against invasion of the home, the church, the school.” Their fear thus “insulates the conscience against a sense of wrongdoing in carrying out a policy of segregation.”

For those with their backs against the wall, however, the threat is very real. Because the use and threat of violence is the tool of all forced division, Thurman writes:

“Within the walls of separateness death keeps watch. There are some who defer this death by yielding all claim to personal significance beyond the little world in which they live. In the absence of all hope ambition dies, and the very self is weakened, corroded.”

Thurman’s portrayal of the links between segregation and the fear of death masterfully demonstrate the winding pathways from cultural ideologies, through politics and policies, into the structuring of places, the inclusion and resourcing of particular bodies in and through places, and the movement back into the depths of the self. Place and one’s inclusion within places are intimately tied to the formation or destruction of a sense of belonging, identity, and self-worth.

Thurman’s genius is to uncover how the restoration of the heart, too often excluded on the left as irrelevant to socio-political revolution, is an essential foundation for forging a politics of love. For him, the assurance that one is a dearly beloved child of God is “the answer to the threat of violence—yea, to violence itself.” One who can rest in the belief that they bear the image of God and who possesses the knowledge that God cares for them as the sparrows and lilies of the field receives in the same moment a restored sense of belonging, the freedom from fear, and freedom from the will to do violence. Indeed, the final power of fear is not its ability to bring death, but its power to steal one’s ability to live freely from one’s own moral center and convictions and to enter into the joy of relationship with other. Jesus provides the oppressed, and oppressors, with that freedom.

Thus psychologically liberated, Jesus calls his followers to enter a lifestyle centered on “the love-ethic” which sees through the spatial divisions imposed by whiteness to act upon the knowledge that “every man is potentially every other man’s neighbor.” By restoring neighborliness, the love-ethic, rooted in the inner spiritual freedom of the knowledge of being God’s beloved, transforms place from violence to community.