A Theory of Theories of Change, Part I: A Theory of Reality

a way to think about the ways anyone talks about how things are, how they should be, and how they think we should get there (Theory of Change Series)

Hey friends!

I’m always trying to figure out the right balance of topics around here. I know many of you got to Toward Solidarity thanks to recommendations from friends at more exclusively spirituality-centered newsletters. Others are here because of you’re a solidarity person: you’re here for the revolution and want to talk politics in theory and practice. Like me, whether you lean more toward action or contemplation, most of you long to hold them together in richer ways. Some of you are just here because you know me from childhood or college or somewhere I’ve worked or somewhere else along the journey. I love this mix! Honestly, I’ve mostly just written what’s on my mind. But I do want to be intentional about curating the right balance and integration.

Much to my pleasant surprise, a post from last summer titled “A Few Observations on Theories of Change” is one of the most engaged with newsletters I’ve sent out. I cheekily subtitled it a “diatribe on diagrams” but really its just a set of observations on the kinds of visualizations provided by theories of change which I felt could be lumped into a few categories. It was fun for me and apparently interesting to enough of you. Which is lovely because I’d love to write more in that vein.

If someone talks about a theory of change, they mostly talk about their theory of change. More often people deploy one or more theories of change without realizing they’re doing so. Very rarely do I see people write about theories of change as such—from a higher-level comparative vantage point. That’s what I’d like to do.

So picking back up where I left off last summer, this will be the first of a half-dozen or so newsletters loosely organized under the heading Theory of Change Series. I’ll weave them in and out with posts written in other styles on other topics, as you’ve hopefully grown accustomed to around here. Ultimately all of it is offered in the spirit of living toward solidarity.

Without further ado…

Consciously or not — whether they be politicians, nonprofit community development professionals, transnational corporate executives, Alinsky-tradition organizers, meditation teachers, electoral campaign consultants, street-corner evangelists, mainstream journalists, guerilla revolutionaries, impact investors, parish priests, elementary school teachers, co-op cultivators, social workers, social influencers or socialist party members — everyone doing something to make the world different than it currently is has a more or less coherently integrated web of convictions about the subjects I’ll outline today.

I see my “Theory of Theories of Change” as a tool for helping make sense of a bewildering buffet. Lots of people talk about changing the world. It’s a vague enough phrase to make it sound like Bill Gates and Angela Davis have basically the same thing in mind. Make things better! But better in what way? From and toward what? Which things need to be better? Make better how?

For the sake of a shorthand, let’s call these different approaches Theory of Change Camps (aka, TOCCs so I don’t have to type so much).

Like any model, mine has limitations. It reveals but by the nature of models also obscures. There are plenty more questions we could pose. There are massive and fiercely debated subjects inside of each topics that I’m glossing past. For example, the domain “Structural” includes — for starters — economic/business systems, political/public systems, and civil society and religious systems. A very important question is: how are these structures best related to one another? Is the relationship more one of collaboration (as I was primarily trained to think in my seminary’s community development classes), confrontation (as some schools of community organizing would argue), control (as either megadonors and lobbyists on one hand or Marxists on the other hand would have it) or stark division (as a libertarian might believe)? This kind of debate, important as it is, isn’t approached directly by my framework. Nonetheless, I think you would end up with a decent sense of how any TOCC would approach that subject if you thought through the prompts I suggest.

In many cases people and their organizations haven’t actually considered much of this and almost never all of it. Much of it will be implicit but still discernible, as much from what a TOCC says as what it does. Our job is to be detectives, finding clues and piecing together the story they tell.

So whether you’re being recruited right now to make phone calls for a presidential campaign, trying to decide which direct service ministry to volunteer at with your family, attempting to make sense of all those corporate philanthropy claims, or starting to organize members of your church or neighborhood for a local policy campaign, my hope is that this provides you with a way to climb up to a higher vantage point from which you can gain a deeper understanding of why each TOCC thinks change should happen in the ways they’re preaching and practicing (which may or may not be the same thing).

Alternatively use this as a road map for fleshing out your own theory of change! We’re often dissatisfied with the way things are, but don’t have the tools to think through a positive vision of alternatives or how to proceed with doing something about it. This model does not give answers or presuppose one right theory. It just helps us ask better questions and remain open to revising as we go. The goal here is to map the terrain any theory of change covers. Ultimately, I hope it helps you become a bit more intentional with how, where, and why you (and your people) do what you do.

A Theory of Reality

To understand a theory of change, you need to understand how it’s adherents see the world and their place within it.

Theories of change are rooted in a mental model of how the world (particularly the social world) works. This theory of reality may flow from whatever the “common sense” is for a particularly community, culture, or ideology. These questions help us understand why someone is angry/hurting/loving/dreaming about what they’re angry/hurting/loving/dreaming about and why they want what they want. With each of the questions below, pay attention to the kinds of values and ethics to which a TOCC wants the world and their own actions to conform.

1. What are things like?

The sociological question. This is the context setting that’s also a problem statement. What’s on the ground? What’s gone wrong and what do we have to work with? Every TOCC has their way of describing the current state of the world. This includes but goes beyond the daily news. However comprehesively, it attempts to make sense of the patterns, deep system structures, and the mental models driving the events that show up in the news—the “thick” present. Likewise the “level” of society at which a TOCC answers this question is telling. Does it focus on a condition that’s local, national, global? What does that level of focus, in and of itself, say about their theory of how the world works and how to change it? Their description of the world will also reveal if a TOCC is specific to a particular issue (street violence, primary schools, immigration, inequality) or if it believes itself to be providing an approach transferable to many or even any issue or community. The way a TOCC describes what things are like tends to focus on identifying what’s wrong with the world. Organizers, pessimistically, call this “the world as it is.” A TOCC is also likely to have some perspect on what is going right and, thereby, highlighting available resources that can be used for change-making (again, this is transferable across ideologies, so “what’s going right” could be anything from the latent assets in dispossessed communities in the case of Asset-Based Community Developers to the policies of Hungary’s fascist regime for Christian Nationalists).

2. How did they get like that?

The historical question. This is the causal dimension. What led to things getting to be like this? As Amos Lee sings, “what’s been going on around here?” How far back does that history go? Who is involved? Who is not included in the story? Who are the heroes and villains? Do they/you focus on individuals, cultures, systems? A TOCC’s theory of how things went wrong already foreshadows their solutions.

3. What else should they be like?

The moral imagination question. In organizing, this is what we call “the world as it should be.” Theology might call it the eschaton or the Kingdom of God. Philosophy might call it telos. It attempts to describe where a TOCC is trying to take us. What do we want for ourselves and/or others? What do we long for? What do we need for this pain to go away, for our lives to matter? What is our definition of “better”? Of the change that we want for the world? There’s a massive range of potential continuities and discontinuities TOCC’s hold between the vision and the present. It may or may not even be articulable (as with the “otherwise” longed for in Black critical theory).

4. How do we get there?

The strategic question. If the previous questions are often “below the water” of the TOCC iceberg — “presuppositional” to the content more explicitly discussed — then this is the part of the iceberg that pokes above the water. This is what people say when they finish the sentence, “We are changing the world by _______.” The solution applies the insights from the previous three questions to develop a plan for making transformation that gets to our desired future. Now, that past sentence assumes that there is always logical continuity between how people describe their problems, preferences, and solutions which obviously isn’t always the case. All of us hold contradictory ideas, and sometimes those things bump together in ways that produce answers that should produce cognitive dissonance but for some reason don’t. Nonetheless, a TOCC’s strategy is their bridge from the world as it is to the world as it should be. Both the “Domains” and “Strategy and Tactics in Theory” are ways to unpack this question in more detail.

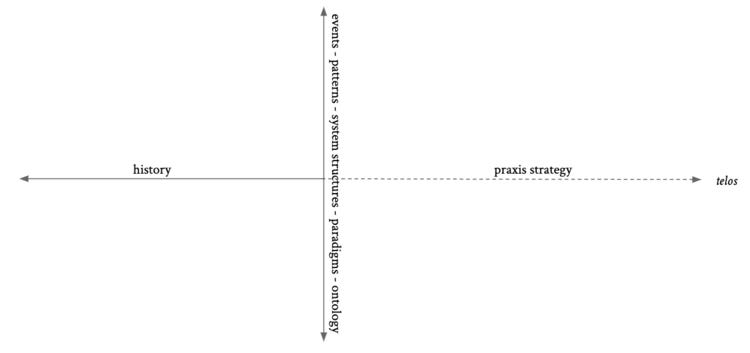

These first four questions could be represented graphically like this:

A TOCC sits at the intersection point of two axes in the thick present condition of things. The horizontal axis is the time dimension. They look back with their theory of history (“how did things get like this?”) and forward to a different future (“what should things be like?”) in which, through the application of their strategy (“how do we get there?”), the things they care about changing have been changed. The vertical axis is what I’m calling the “thick present.” The present moves downward from events to patterns, into the structural realm, the cultural paradigms that produce those structures, and the deep ontological roots of things. Seeing the present in those terms is what’s called a “systems view” of the what is (“what are things like?”). Now, I don’t mean to imply that time itself is linear or that some TOCCs won’t have different understandings of time than the modern progress paradigm — this isn’t a theory of time, just a visual for how TOCCs are situated with respect to these questions.

These last three questions are updates from an earlier version. I think these are crucial at getting below the service for helping us understand where the answers a TOCC provides come from in the first place.

5. How do we know?

The epistemological question. This is about where a TOCC goes for the information it uses to build its picture of reality. How do we come to know what things are like, how they got that way, what would be better, and how to make it so? Are our answers to these questions based on the theories of one particular person or school of thought? Are they (ostensibly) purely data-oriented? If so, whose data and whose interpretations of that data? Is the bible the sole authority for how they see the world and chose their course of action? Or are they (ostensibly) focused on listening to the personal testimonies of a particular group or demographic of people? Did we develop them from reflecting on our own experience? Is it some combination of these, and if so, how are various sources related to each other? Is it just a Youtube end times prophet/conspiracy theorist? The videos Aunt So-and-So keeps sharing on Facebook? As someone (probably) said, epistemology is methodology. Where knowledge about the past, present, future, and solutions comes from is likely to determine everything else about a TOCC.

6. Where am/are I/we? And who am I / are we?

The existential & contextualizing questions. This is about situating yourself and your collective. It helps make clear how a person, organization, or other group claiming a theory of change positions themself within the picture of reality described about. It also is about an individual, organization, or other group identifying their particular function and fit within the broad body of work required to carry out the implementation of a theory of change. Shoutout to the decolonial philosopher Walter Mignolo for helping me pay better attention to geography—both literal and psychological. “I am where I think,” Mignolo says, subverting Descartes. Did a TOCC emerge from a C-suite in Manhattan or a barrio in Tegucigalpa (ie, on which side of the colonial divide is the TOCC situated)? Or to which of those is it more proximate geographically, relationally, and experientially? Who is the “we” for this TOCC? With whom are they in solidarity? How is that boundaried “we” defined and described? Is there a “them” the “we” is contrasted with? Does a TOCC position itself as an insider or an outsider to the problem they are trying to solve? If so, in what way? How do adherents (or you) identify themselves in terms of race, class, gender, nationality, sexuality, religion or life experiences or do they ignore some or all of these? Another dimension of these questions has to do with aptitude. Many theories of change recognize that they are one contribution to a much larger web of strageties needed to fully bring about the world they want. Where do they locate themselves within that larger picture? Often the approach a person or organization leans into has to do with what they see themselves as particularly good at, passionate about, dispositionally comfortable with, called to do, or qualified through experience for. How does their theory of change reflect these considerations? Much much more could be said on this to be sure.

Work through these questions for yourself or with another group in mind. Run speeches from the RNC and DNC through this gauntlet. What about your local church? Or a nonprofit in your area you either like or are confused by? If the answers are totally opaque, read more of what they have to say, look closely at the continuity or gap between what people say and actually do, and — if all else fails or if you have the courage to do so — ask someone in a TOCC to coffee and see if they can answer these questions themselves.

Next time we will unpack the domains, the movement of theory into strategy, tactics, and actual actions, and the ways TOCCs build reflection and iteration into their approach—or not.

Thanks friends. Let me know in the comments if you have any thoughts!

Hey Nathan, some good meaty thoughts here. Appreciate your blog is trying to raise bigger picture issues about TOCC’s, as you point out, the epistemological issues are important and not often considered. However for what it’s worth, James Davison Hunter, an author in this jungle, has a bit of a following down here in New Zealand. I like his thesis that a numbers approach to changing the world is dumb (more evangelism = more Christians = more influence for good = world is changed). We have been doing this for centuries and things are getting worse. His alternative theory that change is effected by networked elites is not palatable to many Christians, but you can certainly see evidence for this in contexts like 18th century UK and the Clapham sect. We are following the US presidential elections with interest down here in the South Pacific, the result will affect the whole world. Recent events are giving us renewed hope…! 🙂🙂. Regards, Gray